Constructed in 1248 upon the command of Louis IX, this building was designed to be grander than any other church in a blatant declaration of the piety and prestige of the French monarchy. Before delving into the specifics of Sainte-Chapelle, I find it appropriate to provide a brief biography (and backstory) of Louis IX, since he did largely initiate the Rayonnant era and many other Gothic trends.

The King of France reigned between the years 1226 and 1270, which was an unusually long span of time given the Middle Ages, and he was well-known for his fairness and piety–even being referred to as “the model Christian king” and St. Louis (he was canonized in 1297). In the year 1239, it is believed that Louis IX bought sacred relics and even some of Jesus’s crown of thorns from Emperor Baldwin in Constantinople to be placed in Saint-Chapelle. He added to this collection in 1241 with additional relics, including: Jesus’s cross, the Holy Spear, the Holy Sponge, a nail from the crucificixion, and the robe and shroud of Jesus. Later would be added part of the skull of St. John the Baptist.

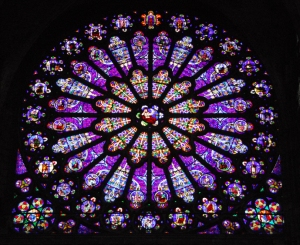

Most of the stained glass at Sainte-Chapelle is aimed to link French royalty to Biblical royalty, specifically to kings David and Solomon; many coronation scenes are also portrayed, including Jesus's.

As for the actual building of Saint-Chapelle (constructed 1241-1248), the structure is actually smaller than most despite its lavish interior. Also unique, the flying buttresses are in fact attached to the support columns inside and invisible on the outside, making any technical structures invisible and giving the cathedral an ethereal and weightless atmosphere. Since there are no obstructions, light flows in uninterrupted, and under the full beams of the sun one would think himself inside a jewel or heaven.